Outreach

Ant food choice

This program works well with 1st-5th grades. The number of foods can be altered to accomodate different grades. Working in pairs works well for students in younger grades.

Overview: This life science unit investigates food selection by ants. Experimental design is emphasized. Students work singly or in pairs to select foods, place them on 'trays' and count the number of attracted ants. Data are analyzed as a class. Steps in doing experiments are reviewed and reasons for variation in data are discussed.

Specific goals of the program:

1. Let students run unique food choice experiments using ants in their school yards.

2. Have students understand that they are doing all the steps in scientific research (i.e., background knowledge, generating a hypothesis, collecting replicated data, data analysis, and drawing conclusions based on results). We discuss why there is variation in the data. Students are encouraged to consider themselves as scientists.

3. Teach students an experimental design (Latin squares lay-out) and discuss other types of research that might use this design.

Methods and Materials

pdf downloads:

- Teacher's Guide with detailed methods, including background information and data analysis.

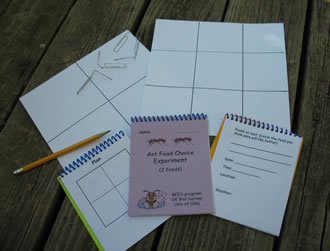

- Student research notebooks (stack up all pages, then cut in half through the horizontal and vertical middles, producing 4 notebooks - bind along the top edge). Also includes a number line, graph paper and evaluations.

[back to top]

The program begins with a discussion about which foods people like (including the class voting among a few foods, each selected by a student); then the students are asked how they would figure out what a pet likes to eat. (e.g., give the pet choices of different foods to select). Students learn how to make Latin square designs and choose (individually or in pairs) foods to test with ants (foods can be supplied or can be from the students' lunches). Students hypothesize which of their foods will be preferred by ants, then we all go to the schoolyard and set up the experiments. The design, predictions, and data are recorded in a spiral-bound notebook.

After an hour or two, we return to the experiment, count ants on each food and clean up (blowing ants off the 'trays' before their feasts are discarded). We discuss results as a class in the classroom (where there is a chalkboard). First we check to see whether everyone got ants (and discuss why not everyone got ants), determine who got the most ants and what the preferred food was, and discuss why individuals/teams didn't all get the same data (reasons include: habitat, nearness to nest(s), exposure - including sun or shade, types of ants,...). Data are tabulted by listing foods and recording the most and least preferred food for each experiment. Students determine which are the most and least favored foods from the cumulative data.

We ask students to raise their hands if their predicted food was more popular in their own experiment. Explain that wrong predictions are fine and that this is how we discover new things.

If foods are supplied, students can read the nutrition labels and determine whether foods is high in protein, sugar and/or fats and whether ant prefer certain nutritional categories. For lunch foods, the nutritional content can be added by the instructor (hopefully, with student input).

We go over the steps that the students took in doing their research.

Lastly, we hand out short evaluation forms and stickers 'I am an ant scientist'.